Skin color does not equal diversity

…. But it’s a start.

Currently, there’s a wave of conversations spinning around diversity and medicine — however, when not grounded in facts, they risk sounding like corporate jargon punctuated by hollow buzzwords.

As a medical illustrator of Asian American descent, I grew up consciously aware of the diversity of my surroundings… or perhaps in reality the lack thereof.

I remember when I started a new primary school, I was often mixed up with the one other Asian girl in my class. As a 10-year-old, I wondered if my external appearances, particularly my skin color and Asian traits, were my only identifiable characteristic.

I want to unpack the meaning of diversity by having a conversation about skin color (yours and mine). How looking at skin color in medical illustration gives us a glimpse into the questionable state of our healthcare system.

“But what really is diversity… and why does it matter in medical illustration, which should be “objective”?”

The Beginning

My name is Tiffany and I am a medical illustrator, which at the core means I love anatomy and art and will most likely get excited if I see a flattened raccoon on the side of the road. Like most other medical illustrators in the field, I found myself attracted to the mesmerizing classical illustrations I saw in old anatomy atlases. The red watercolors leapt out of the yellowing pages — splaying open the human body into a million tiny layers. It was educational, of course, but also it was indulgent eye candy.

Pernkopf anatomy: Atlas of Topographic and Applied Human Anatomy: Head and Neck. Source: Biblio

And when the books weren’t enough, I forced my parents to bring me to the local Bodies exhibit. As a young teen mildly obsessed with dead animals and blood (don’t ask, it was the puberty), I got to see halls upon halls of REAL human bodies that had been plastinated — dissected and displayed for my morbid teenage curiosity.

Blood vessel configuration of a lamb. Source: The Dispersal of Darwin

The Dilemma of Diversity

However, upon starting my Master’s at Zuyd Hogeschool in the Netherlands to study medical illustration, I began to hear a more complicated discourse:

The historical standard in medical illustration is majority white, male, young, and able-bodied.[1]

Only 4.5% of medical textbook images feature patients with dark skin colors.[2]

In 2021, only 18% of medical images from The New England Journal of Medicine showed figures with non-white skin colors.[3]

A 2017 study showed that only 36% of images in anatomy textbooks represented women.[4]

On average, men are portrayed 2.5x more than women in textbooks.[5]

Breaking barriers in medical illustration

This year is the first year that the Association of Medical Illustrators is holding a Diversity Fellowship, sponsored by Johnson and Johnson, to increase diversity of representation within medical illustration to combat these depressing statistics. Particularly, this “Illustrate Change” library features medical conditions depicted on patients from minority groups. When I was chosen to be one of the ten fellows, I was overwhelmed.

This is it.

This is my chance to contribute my skills to a worthy cause…. and perhaps even influence the canon of medical illustration. After all, what artist doesn’t want to contribute to the huge tapestry of art history?

Don’t get me wrong. I am Chinese American by descent. So the idea of seeing more representations of people who look like me in a white-dominated pool of imagery deeply pleased me. However, time and time again, the conversations around diversity kept narrowing solely to skin color.

Deep vein thrombosis: Lack of representation of medical conditions can impact pregnant women. Globally, due to increased blood pressure, pregnant women are at higher risk for developing deep vein thrombosis. Source: Biotic Artlab

Why does skin color hold such significance when, fundamentally, our internal anatomy remains largely uniform?

Am I reduced solely to my skin color? Isn’t discriminating by skin color its own form of bias? Shouldn’t we as a society aspire to be “color blind”? Isn’t that what true diversity, equity, and inclusion look like?

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL): ALL is a type of blood cancer in children, characterized by the rapid and uncontrolled growth of immature white blood cells, known as lymphoblasts, in the bone marrow. Artist: Ni-Ka Ford. Download the infographic here.

Homogeneity creates bias

Let’s see what happens when we don’t have diversity.

A study of anatomy texts for medical students in the U.S. showed a disproportionate use of the white male body as the norm, whereas the female body was always used as a secondary comparison.[6]

How do we think that this impacts our implicit biases? And, more importantly, what happens when these biases scale up from medical school and follow the next generation of practicing physicians?

These biases have their own laundry list of consequences.

GENDER BIAS: Cardiovascular disease is under-recognized in women and touted as more of a problem for male patients. Many textbooks do not address how heart disease presents itself in women, which leads to high misdiagnosis rates.[7]

RACIAL BIAS: Black women in America are 3x more likely to die in childbirth than white women due to unspoken bias against black women.[8]

AGE BIAS: Many conditions are often incorrectly paired with their depiction on a standard male male body. For example, osteoporosis affects older women much more than men. Therefore, it is less helpful to visualize osteoporosis on a young male body.

Heart Failure: Heart failure is when the heart is unable to pump blood around the body well enough to meet the needs of the body. Artist: Morium Howlader. Download the infographic here.

With all these biases, how could diversity help us provide better healthcare? To answer this, we must go beyond skin deep and look at diversity through ethnicity.

The Ethnic Lens: Understanding Unique Healthcare Needs

Growing up in the U.S., even with its melting pot culture, it often felt as if there was an “us” against “them” mentality. The people of color (POC) community vs. the Caucasian majority — an ongoing war fueled by political and racial tensions.

However, this approach completely erases the fact that different demographics are impacted differently by disease. This can arise from genetic predispositions, cultural factors, socio-economic status, and historical injustices.

Let’s look at some of these diverse realities:

Skin Cancer in Caucasian patients: Certain types of skin cancer, such as melanoma, have higher incidence rates among Caucasians, particularly those with fair skin, light eyes, and light hair, compared to other racial and ethnic groups.[9]

Diabetes among Native American populations: Native American communities have a higher prevalence of type 2 diabetes compared to the general population. Factors such as genetic predisposition, limited access to healthy foods, and historical trauma from colonization contribute to this disparity.[10]

Breast cancer in Ashkenazi Jewish women: Ashkenazi Jewish women have a higher risk of carrying BRCA gene mutations, predisposing them to breast and ovarian cancers.[11]

Liver disease in Hispanic/Latino populations: Hispanic/Latino individuals are disproportionately affected by chronic liver diseases such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and hepatitis C. Factors such as genetic predisposition, high rates of obesity and diabetes, and limited access to healthcare contribute to this disparity.[12]

Tuberculosis (TB) in immigrant and refugee populations: Immigrants and refugees are at higher risk of TB infection due to factors such as overcrowded living conditions, limited access to healthcare, and pre-existing TB prevalence in their countries of origin. Language barriers, cultural beliefs, and fear of deportation may prevent their timely diagnosis and treatment.[13]

Sickle cell anemia and hypertension in African Americans: African Americans are disproportionately affected by conditions like sickle cell anemia and hypertension. Yet cultural factors can prevent them from seeking the healthcare they need. For example, mistrust of the healthcare system due to historical injustices such as the Tuskegee Syphilis Study can historically lead to reluctance to seek medical care.[14]

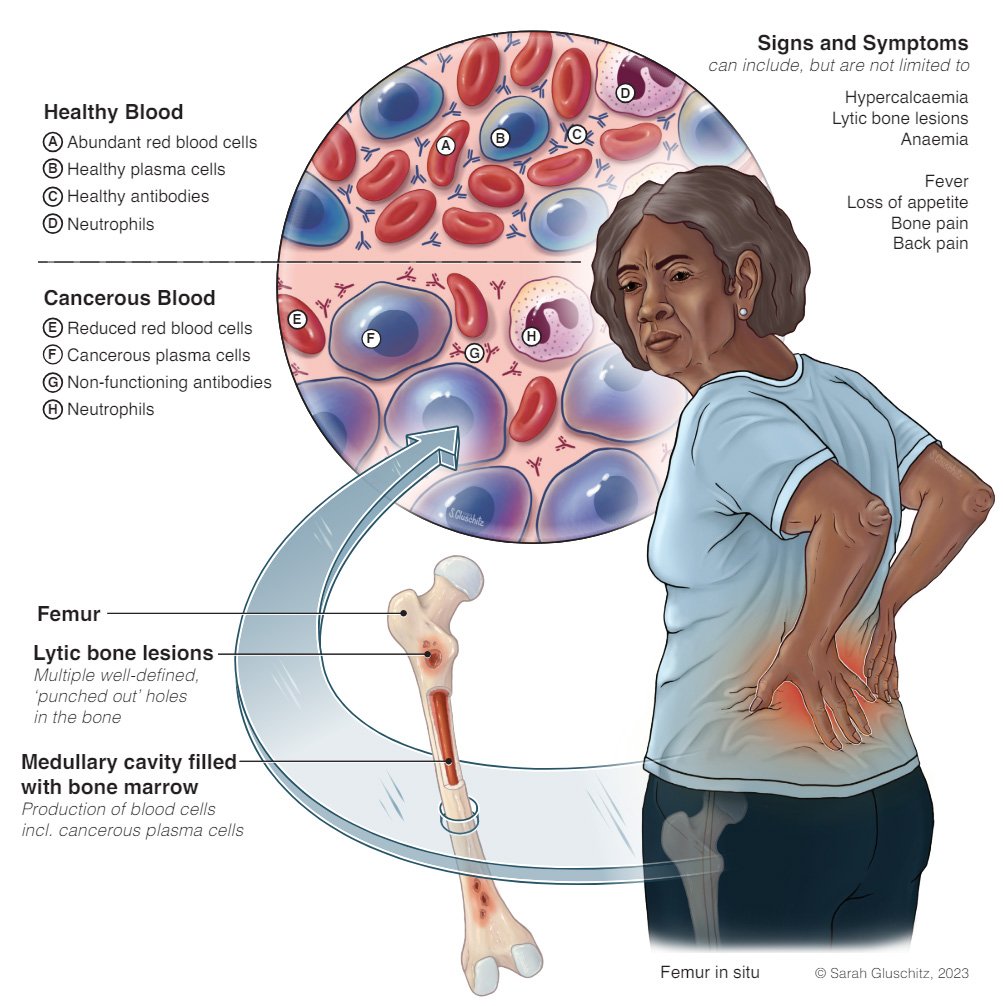

Multiple Myeloma: Patients of African descent may be more susceptible to multiple myeloma, a rare form of blood cancer. Artist: Sarah Gluschitz. Download the infographic here.

In fact, to look at skin color is not superficial. It reminds us that our medical histories are impacted by our diverse ancestral backgrounds.

The role of Medical Illustration

Medical illustration’s existence serves as a bridge of communication between healthcare professionals (HCPs) and patients. It helps HCPs translate complex medicine into understandable bits of information.

If these illustrations lack diversity, they can easily become vehicles that perpetuate bias, which we’ve seen has damaging effects on healthcare.

By being active participants in the diversification of representation in medical illustration, we can:

Improve Cultural Competency: Illustrations reflecting diverse ethnicities help HCPs better understand and connect with patients from various backgrounds. This leads to personalized care = better care!

Improve Health Literacy: Visual representations that resonate with diverse communities can motivate individuals to make smarter choices about their health.

Combat Gaps in Healthcare: Addressing diversity gaps in medical illustration is an important step towards promoting healthcare that is catered towards each individual demographic group.

The Forbes featured campaign “Reframing Revolution” focused on creating a diverse women’s healthcare medical illustration library. Illustrations by Biotic Artlab. Client: Peanut

Ultimately, recognizing diversity improves the quality of healthcare

Diversity is not about meeting a corporate quota but rather acknowledging and embracing the rich tapestry of human experiences that should shape our approach towards healthcare. A one-size-fits-all occidental mindset will only fail our current society.

“So yes. Maybe a visible trait like skin tone ALONE does not equal diversity… but it is a start to a bigger conversation that allows us as a society to address our implicit biases that involve not only race but also gender, age, athleticism, and more.”

With diversity of representation in medical illustration, we can share more knowledge about the realities of our diverse world. In doing so, we honor our differences and better serve our communities.

Want to keep the conversation 👋 going?

What are your thoughts on this? How can we further expand our understanding of diversity in healthcare? Contact me at info@biotic-artlab.com.

Tiffany Fung is a medical illustrator and co-founder of Biotic Artlab. Outside of giving herself carpal tunnel through drawing, she is an avid climber who wishes to use medical illustration to contribute back to the climbing community.

References:

[1] https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/10/081015132108.htm

[2] Jawaid, M., Ashfaq, S., Nawaz, S., Ali, S., Usman, M., & Bhatti, A. (2020). Gender Representation Among Authors and Editorial Board Members of Pakistani Medical Journals: A Cross-sectional Study. Cureus, 12(7), e9468. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32753112/

[3] Khosla, N., Carpio, A., & Serrano, L. (2018). Gender representation in medical textbooks: A comparative analysis of five specialty and three subspecialty disciplines. Cureus, 10(2), e2197. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29501717/

[4] Lofters, A. K., Slater, M., & Nichols, D. (2018). Thematic analysis of Canadian medical school diversity equity and inclusion reports. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 30(2), 199–209. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0277953617301879

[5] Assael, L. A., Sussman, G. L., Lewis, C., O’Brien, D., & Kazim, M. (1992). Comparison of cephalometric norms between Chinese and Caucasian-American adults. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, 101(6), 465–470. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1411693/

[6] Bailey, L. J., Johnson, R. A., & Hu, J. W. (1992). Ethnic variation in malocclusion among American Negroes, African-born Negroes, and Nigerian-born Negroes. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, 101(6), 539–543. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1411693/

[7] Ha, T. C., Ng, S., & Kam, J. (2008). Incentives and disincentives to participation by medical students in a longitudinal integrated clerkship. Medical Education, 42(1), 22–28. https://asmepublications.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03150.x

[8] Villarosa, L. (2018, April 11). Why America’s Black Mothers and Babies Are in a Life-or-Death Crisis. The New York Times Magazine. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/11/magazine/black-mothers-babies-death-maternal-mortality.html

[9] Ahmed, R., & Levin, A. V. (2021). Racial Disparities in Pediatric Eye Care: An Exploration of Prevalence and Social Determinants. Journal of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, 58(1), 14–22. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9345197/

[10] Office of Minority Health. (n.d.). Diabetes and American Indians/Alaska Natives. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/diabetes-and-american-indiansalaska-natives#:~:text=American%20Indian%2FAlaska%20Native%20adults,whites%20to%20die%20from%20diabetes.

[11] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, August 6). BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutations in Jewish Women. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/young_women/bringyourbrave/hereditary_breast_cancer/jewish_women_brca.htm

[12] Office of Minority Health. (n.d.). Chronic Liver Disease and Hispanic Americans. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/chronic-liver-disease-and-hispanic-americans#:~:text=Both%20Hispanic%20men%20and%20women,their%20non%2DHispanic%20white%20counterparts.

[13] Cain, K. P., & Benoit, S. R. (2011). Tuberculosis in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Regional Assessment of the Impact of HIV and National Income. International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 15(8), 1058–1061. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3168670/#:~:text=The%20risk%20of%20active%20tuberculosis%20in%20refugee%20populations%20is%20about,immigrant%20populations%20(Table%201).&text=This%20is%20likely%20due%20to,of%20recent%20exposure%20to%20tuberculosis.

[14] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, September 28). Data & Statistics on Sickle Cell Disease. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/sicklecell/data.html#:~:text=SCD%20affects%20approximately%20100%2C000%20Americans,sickle%20cell%20trait%20(SCT).